I cut my hair short several months ago. It wasn’t impulsive, it was deliberate. I was feeling into the femininity that long hair had always carried for me, and I wanted to set that down.

Maybe I thought I could free myself from the story of beauty, or at least loosen my grip on the subconscious belief that being attractive was the safest way to move through the world.

So I cut my hair and dressed down.

What I didn’t realize was that the performance of beauty wasn’t just habit, it was a silent form of currency, and I had abruptly stopped paying. This brought a deep discomfort. Unless I pinned my hair up just right and added a touch of makeup, I felt like an uninvited guest in society’s performance.

Sitting with that discomfort was part of the work. The other part was looking deeper to see what lay beneath.

What I found surprised me, and has been quietly changing my relationship to beauty ever since.

A collective form of presentation

The state of Chihuahua, Mexico, is home to the Rarámuri people. Here I see Rarámuri women moving through plazas in long, full skirts that billow as they walk. Matching blouses gather at the neck and sleeves, stitched from bright colors, trimmed with ribbon. Some wear headscarves, their long hair flowing free or braided down the back.

They are beautiful, like desert poppies in technicolor.

But it isn’t just beauty I’m witnessing. It’s a shared choreography, a collective form of presentation, a rhythm of belonging passed down through generations, where clothing isn’t performance but living expression woven into daily life.

I stand in the plaza, touching the ends of my chopped hair, and begin to see that the discomfort I’ve been carrying may not be about hair at all, but about living in a culture where identity is something you construct alone rather than receive. Where beauty isn’t a shared ritual, but a kind of currency. No inherited adornment, just individuals making it up as we go along, carrying the incredible and disorienting freedom of self-invention.

Still, I want to be clear: the Rarámuri women I see aren’t metaphors or symbols. They are part of a living, ongoing culture with its own deep history of resistance and survival. Through land displacement, violence, and forced assimilation, they continue to wear their flowing colors like banners of refusal. I’m sharing what moved me, but I recognize the limits of my perspective.

What we inherit, what we invent

Without inherited forms of expression or belonging, many of us are left to assemble identity from what’s available, often guided more by market trends than cultural memory. Beauty becomes branding. Selfhood becomes a project.

The result is a quiet and aching dislocation.

And here I am, trying to locate myself within a patchwork of immigration and reinvention, searching for something rooted. What I find is a sense of being that is, yes, patchworked, yes, cobbled together, and yes, made of the very stuff of needing one another.

I come from a family that practices hospitality like a reflex. Sharing is stitched into the shape of our very existence. Our lineage wasn’t passed down in heirlooms or ritual, but you can feel it in a room when someone needs help and we move toward them, not away. Ours is an inheritance of love that holds space. Of emotions that get processed, not repressed. Of generational trauma interrupted- consciously, painstakingly- and replaced with tenderness.

When I offer half of my sandwich to the stranger next to me on the bus, that’s my inheritance. When I have nothing but an ear to listen, and give it freely, that’s my inheritance. My family didn’t pass down who to be. They passed down how to love.

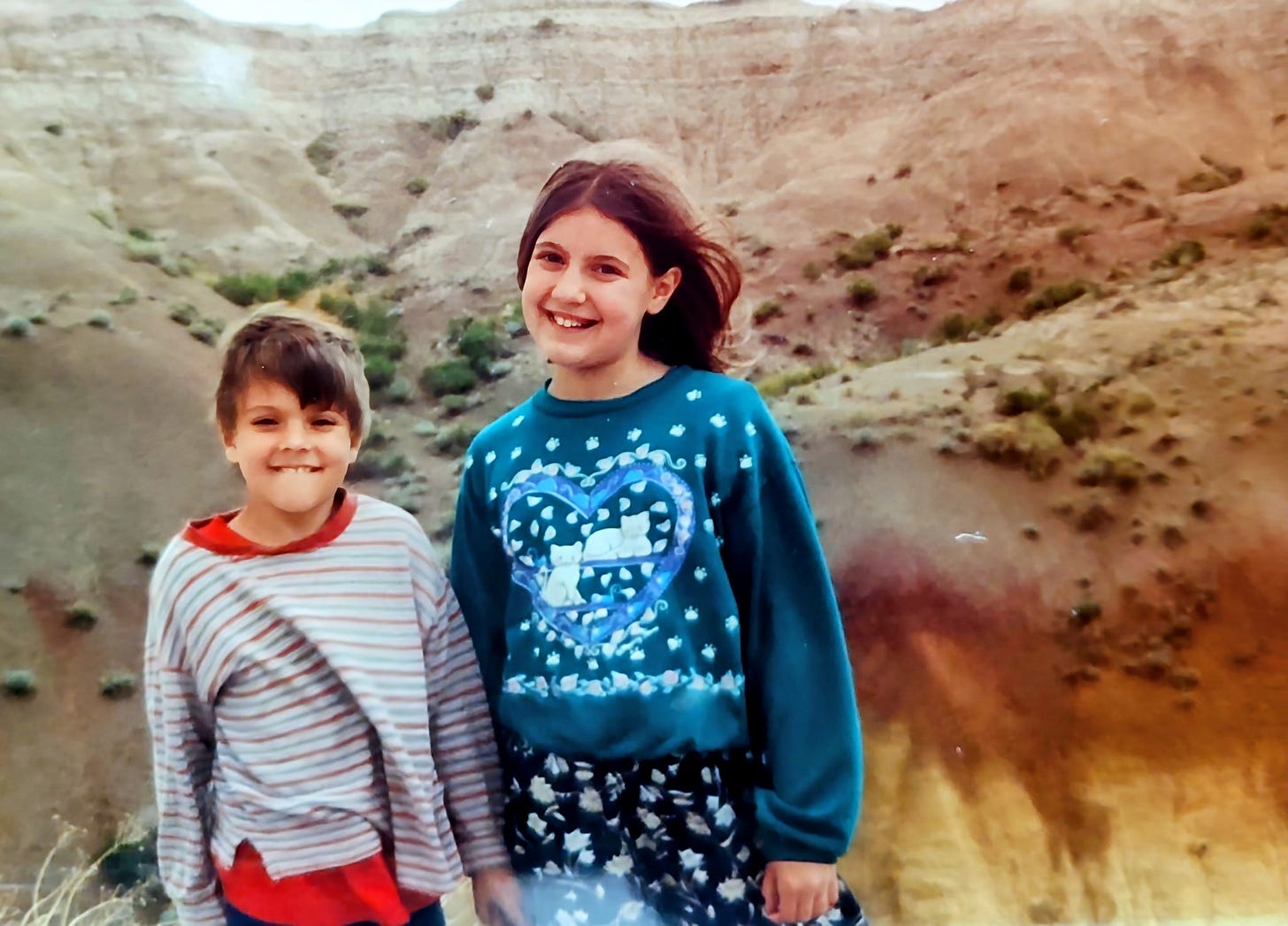

If I could braid all that into my hair- fashion a skirt out of the way my grandma tears up in the face of kindness, or the way my dad shows love by making pizza- if I could stitch my brother’s wit into the hem, wear my grandfather’s curiosity like a charm, my niece’s joy like little bells on my ankles- and then wrap it all up in the strong material of my mom’s tremendous heart, these would be my garments.

Let this be how I move through the world

I think fashioning this outfit might take a lifetime. In the meantime, I was able to fit some of it into a song.

This brings us to track two on the album: Tatterhood. I originally wrote it 15 years ago as a Father’s Day gift, and then rewrote it to hold the broader circle of my family. My brother came into the studio to add his vocals to the mix. It’s a big, layered production, and one I’m proud to share.

Two friends told me they found themselves stuck on track 2, not out of disinterest in the others, but because they kept looping it the moment it ended.

Check it out here. And remember, if you stream it on Spotify I don’t make any money, but if you listen on Bandcamp and choose to contribute, I do.

Love the thoughts here as I've loved the album. Thanks for this!

You have a beautiful heart, Hana.